Wickwire's Horses for Gold

LOGLINE: The true history of Byron F. Wickwire, a Wyoming Rancher who, in 1897, attempted to earn his fortune driving 80 wild horses from Bonanza, Wyoming over 3000 grueling miles to Dawson City, Yukon Territory.

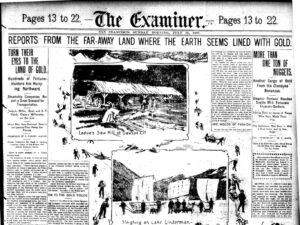

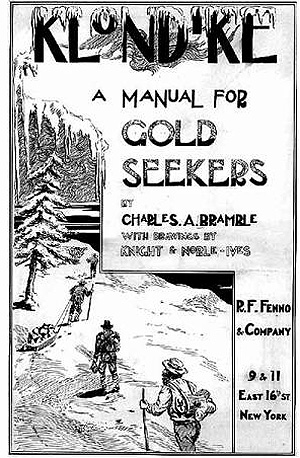

The stories of riches and wealth inspired a great many to risk their lives, enduring unbearable hardships, for fortune. This sudden mass response was due in part to: Unemployment and Economic challenges in the U S at the time; higher prices and demand for gold; and the misleading media promotions that the Klondike was “just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible.”

The prospectors were mostly Americans or recent immigrants to America and many of them had no survival skills or experience in the mining industry.

The migration of these prospectors caught so much attention that it was joined by outfitters, writers and photographers.

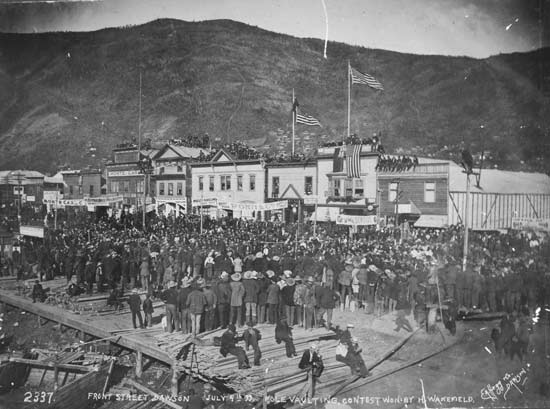

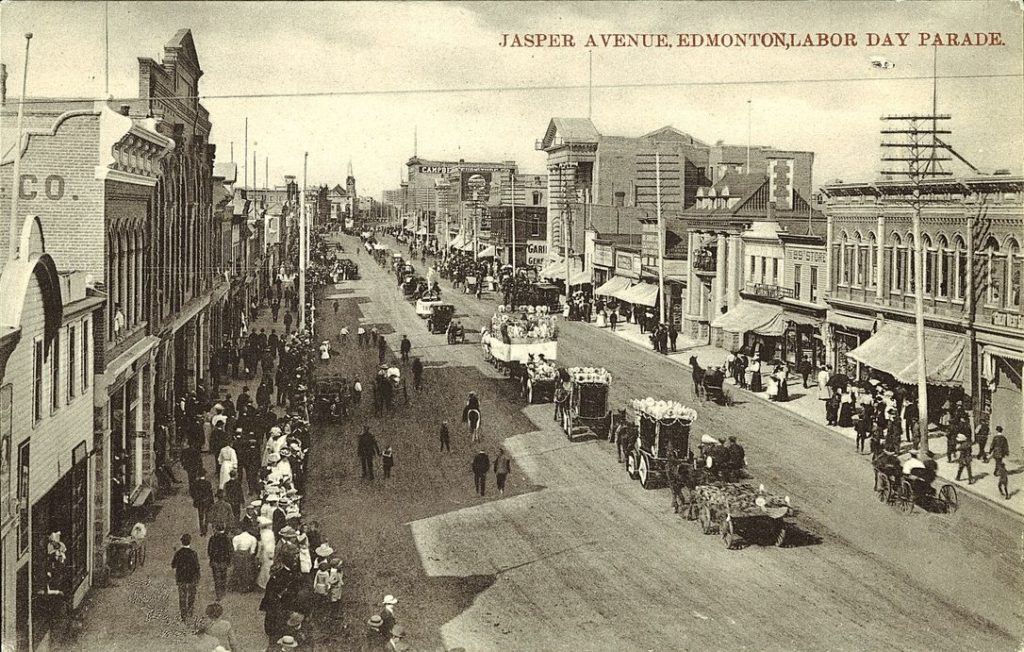

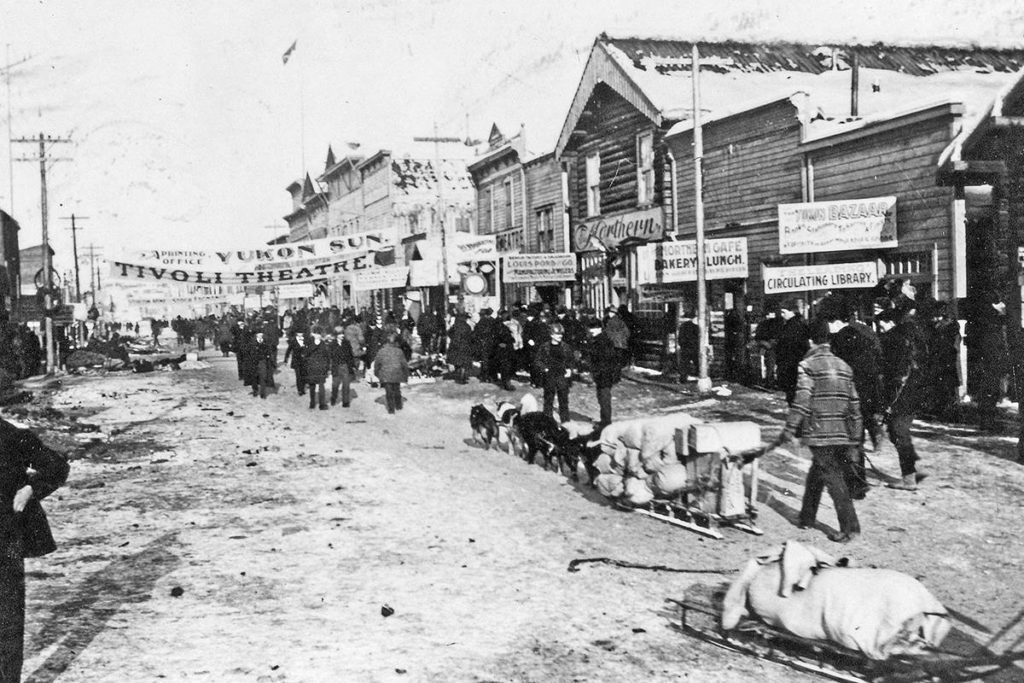

By 1898 Dawson City had grown to house approximately 30,000 people, and a demand for supplies grew that inspired others to attempt to make their fortunes accommodating the prospectors needs.

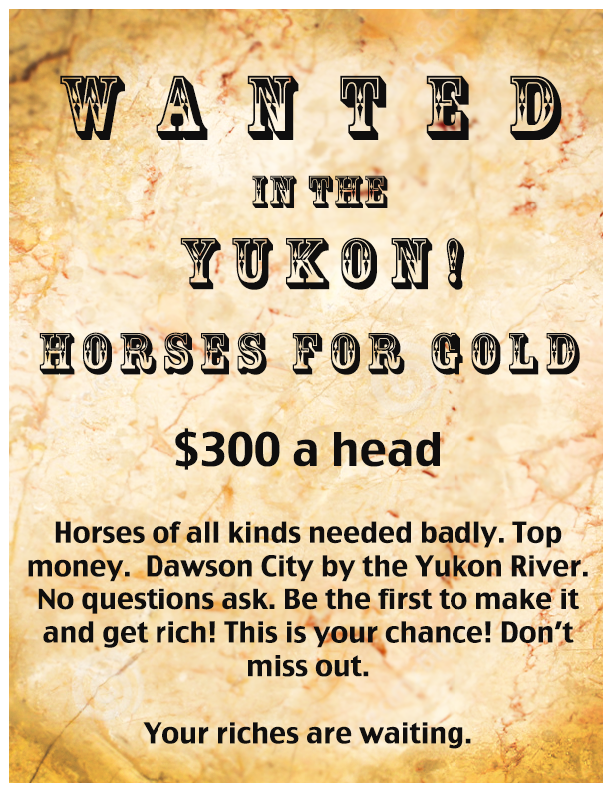

One of those needs was for pack animals, and rumors floating around western states like Wyoming were that they were paying top dollar for horses… all you had to do was get them up there.

_______________________

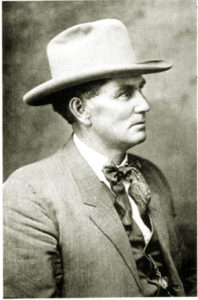

Byron F. Wickwire was born in New York state in 1863.

When he was 12 his family moved to Nebraska and homesteaded in Red Willow County on Beaver Creek. Their first home was a sod house and Young Byron spent most of his time in the saddle riding after cattle for neighboring ranchers. At one point, Cheyenne Indians left the reservation and killed 10 people on Beaver Creek, one man within a mile of the Wickwire Farm.

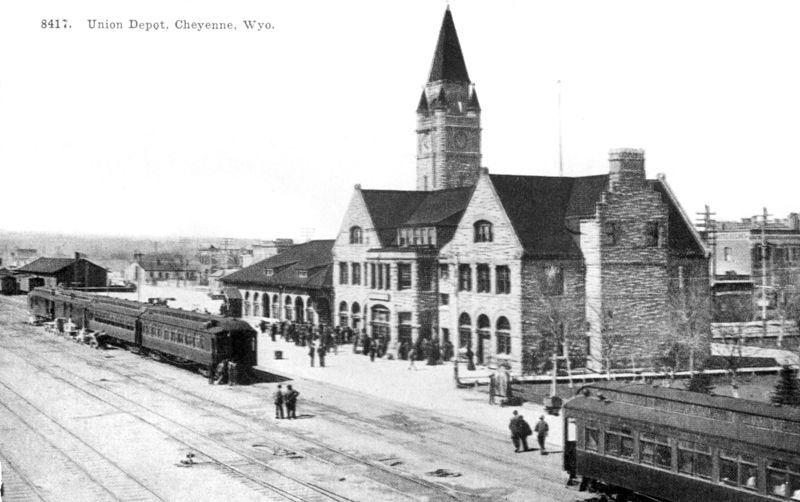

After the death of his mother in 1882 when Byron was just 19, Wickwire headed west to Cheyenne, Wyoming, where he heard of the Bighorn basin of Northern Wyoming, which had only recently been discovered by the big Cattlemen.

Wickwire moved on to Rawlins, Wyoming then worked his way to Lander with a freight outfit. He met John Lumen who hired him to help take a herd of 7,000 cattle into the mountain-encircled Bighorn Basin.

The cattle were dropped on the Bighorn River, a cabin was built and young Wickwire spent the winter looking after the Lumen herds.

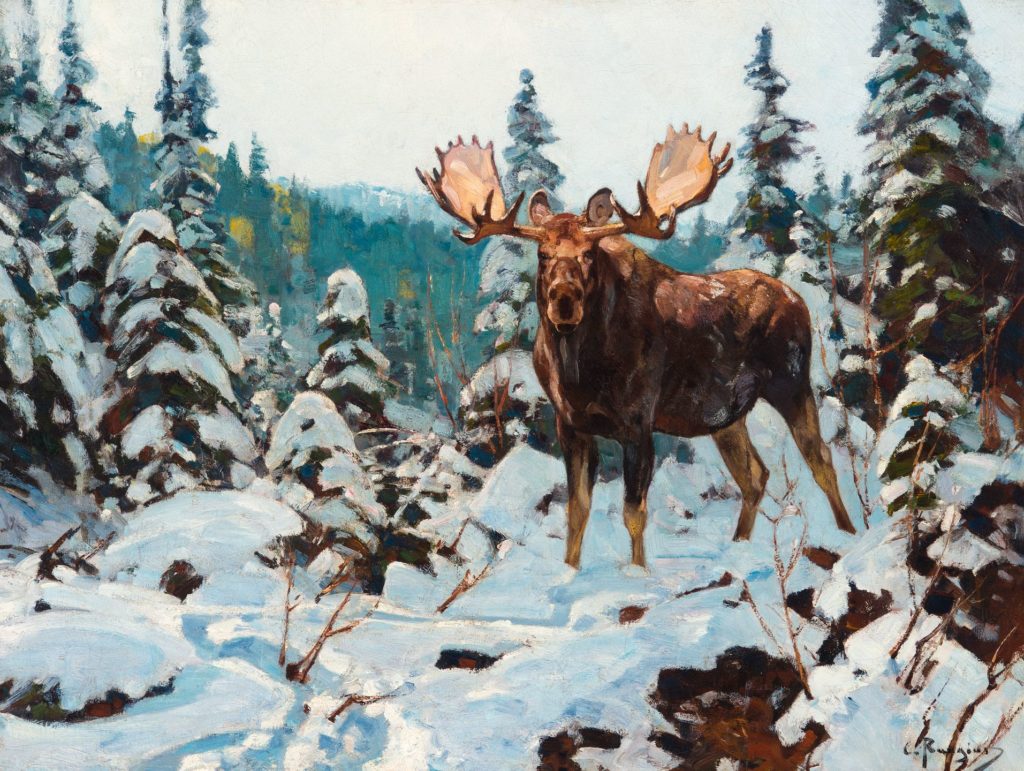

Tall luxurious bunch grass covered the Basin and the Lumen cattle wintered well. Buffalo, elk, bear, deer, and Antelope still abounded so meat was plentiful.

The next winter Lumen sent Wickwire with a herd of horses to Paint Rock Creek on the western slope of the bighorns Wickwire built a cabin of cottonwood logs, the second in the PaintRock-Medicine Lodge Valley. That area became Wickwire’s home for many years.

Wickwire was foreman for Luman until 1886, the period when the cattle kings flourished, their herds ranging the basin. The hard winter of 1886-1887 brought crippling losses to the cattle barons, contributing to the breakup of the cattle kingdoms. Settlers were coming in with their plows and shovels, and soon the range belonged to the small cattlemen.

B.F. Wickwire, twenty-one in 1884, filed on a homestead, a beautiful spot where the Medicine Lodge Creek tumbles out of a mountain canyon. He lived on his homestead for a part of each year.

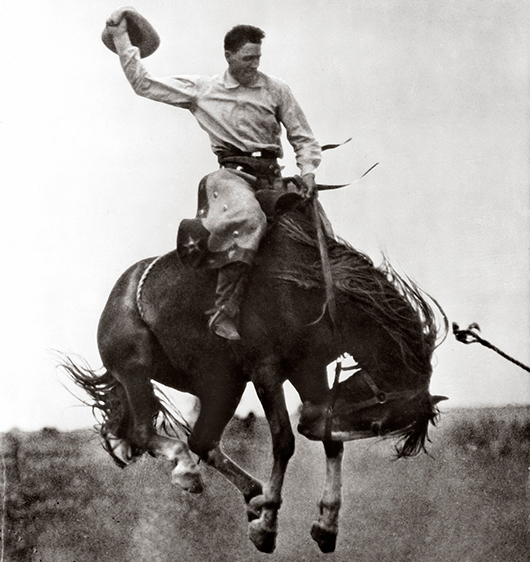

Wickwire’s riding and roping expertise were utilized by various ranches of the basin, including the famed Pitchfork Ranch on the Greybull River, far across the basin to the west.

During 1886-1890 Wickwire was appointed a special deputy sheriff of the Big Horn Basin. He was a fiddler and many cowpunchers whirled homesteaders’ daughters to the tunes sawed out by B.F. Wickwire.

He courted May Rawson, a slender girl from California. Her family operated a store in Hyattville, a cowtown founded in 1886 just above the confluence of the Paintrock and Medicine Lodge Creeks. They were married in 1896 and Wickwire took his bride to his ranch nestled at the foot of Medicine Lodge Canyon.

This canyon opening had long been a favored camping site of the Crow tribe and the sheer bluff above the corrals is embellished with Indian writings and pictographs. Today, the name of Wickwire can also be found on that cliff.

Wickwire raised cattle and horses and luck seemed to be with him. He had land and livestock and a wife he adored— so much so that he rebelled at the sight of May doing the hard tasks of a rancher’s wife.

That rebellion contributed to his decision to seek the goldfields of the Yukon when news of the strike there drifted to Wyoming. Money – some quick profits – would alleviate some of those hardships for May, he thought.

That wasn’t the whole of it, though. Byron F. Wickwire had been nurtured on adventure, and he savored it. If the opportunity for excitement appeared, Wickwire needed no prodding.

HORSES FOR GOLD

In 1897, WHEN Lon Taylor returned from a trip to Billings, Montana, his enthusiasm for a jaunt to the Klondike infected Wickwire, too. It sounded good – not mining gold but taking horses to be sold in Dawson. Horses there, Lon had heard, were selling for $600 to $700 a head. And Wickwire had horses, plenty of unbroken broncs running those-hills and gullies.

Lon had some literature put out by a big Edmonton packer telling about the Edmonton Trail – “The shortest, cheapest, and the best way to reach the richest goldfields ever discovered. Travel safe, fish plentiful, game, no fear of Indians, no hardship. Route has been used by Hudson’s Bay Company for years.”

It sounded simple – start those tough cayuses north and just follow them through. They could manage about eighty head. It would mean an absence of several months, maybe a year. But John Luman, his neighbor, would see that May was all right and would look after his ranch and stock. Wickwire began gathering horses, choosing the strong, the intelligent.

Riding Roman Nose, his favorite buckskin gelding, Wickwire and Lon hazed those mustangs out of Bonanza, some miles below Hyattville, on October 5, 1897. Charlie Olson went along, driving a team on a wagon, loaded with their bedding, tents, and other provisions. Their spirits were high. They should get into Dawson in the spring, just right for a good market.

Although troublesome at first, the broncs soon lined out each day. On October 10 they reached Billings, having traveled 120 miles. Lon had made arrangements to meet a freighter, George Weaver, who wanted to go to the Yukon with them, but they learned that he had gone on. They bought warm clothing and blankets and left Billings on October 18.

Two hundred miles out of Billings and one month after leaving Bonanza, they crossed the Canadian line at Coutts, paying two dollars a head duty on eighty head of horses. They had met no great problems in crossing Montana except for a couple of bad snowstorms.

Sixty miles into Canada they overtook George Weaver with his six mules and one pinto mare, and a French halfbreed called Big Joe. The Wyoming men soon learned that nothing ever bothered George Weaver – he was always laughing and telling tall tales.

At Ft. McLeod they were hit with a long fierce blizzard, forcing them to stay in camp from November 12 to December 13. Keeping the horses together was a big job, but their tough Wyoming mustangs stood the storm very well.

Problems were mounting. There would be more storms, scarce feed and frozen streams. Wickwire, Lon, Charlie, Weaver; and Big Joe loaded the horses on the train and shipped them 300 miles to Edmonton.

Already they were running into men in a hurry to reach the goldfields – stampeders who offered them a good price for horses, but they refused to sell.

EMONTON

On December 16 they unloaded the horses in Edmonton. They had been more than two months on the trail and here they were, at the jumping-off place – with temperatures of forty degrees below zero, lots of snow, and short days.

After checking with local people, wisdom dictated the next move. They found a good pasture and an old house two miles from town, unpacked their gear, and it was two months before they moved on. That time was filled with activity.

The Wyoming horse wranglers joined up with three men from Miles City, Montana – “Dad” Atkinson, his son Charlie, and Billy Hill. Dad was a good carpenter – he made six good sleds and a bobsled. They all worked on harnesses, pack saddles and collars. The younger men broke horses to pack, and to drive on the sleds.

Wickwire was the horse trader, buying and selling. At first the Mounted Police kept a close watch, suspecting the horses had been stolen. B.F. Wickwire became known as the horse-trading Yankee.

During those short cold days they weren’t without entertainment. Many men visited the Wickwire camp to trade horses, to watch those Wyoming punchers break horses, to talk over plans or to exchange news.

There were gatherings at the Royal Hotel, and Edmonton had dances, called “perkies.” where Wickwire was sometimes persuaded to fiddle.

He sent a Christmas package and letters home. In January he received two letters from May, telling him that all was well.

Prices for food and other goods rocketed with the advent of more gold-seekers. Every train brought a load of them, eager to head for the Klondike, but all had to wait for the snow to get heavy enough for a well-packed trail.

There was great discouragement when the true condition of that highly advertised “good road” to Peace River was discovered. The Wickwire party soon learned how-misinformed they had been – not far out of Edmonton there was no more than a poor trail for a dog team.

During early February Wickwire watched more than 150 parties hurry out of Edmonton, most of them ill-prepared. They were chiefly men from the East who knew nothing about caring for horses, packing, or the hardships of trail travel.

THE Wickwire party left on February 14 with their horses in good shape, with strong sleds, good harnesses, warm clothing, and a year’s provisions for each man. They had seventy-three head of horses, working twenty-five of them, and herding the others. Five sleds were loaded with barley, the others with bedding, tents, tools, and other provisions.

Big Joe stayed in Edmonton. The group now consisted of Wickwire, Lon, Charlie Olson, Weaver, Billy Hill and the two Atkinsons. “The best bunch a man could travel with,” Wickwire said later. “Trouble never bothered. them.” That was a plus, for they had plenty of it.

In no way could they have imagined the toil and perils of the next months – or the grandeur of the country with its great rivers and gorges, lakes, mountains , thick timber, and muskeg. And there were many areas of good grass where Wickwire always· said, “Some day there’ll be a lot of good ranches here.” There were wild geese, lakes black with ducks, and they sighted swans and pelicans.

Wickwire was the fisherman and hunter, with no lack of moose, deer, bear, caribou or wild birds. During that long trek he wondered at the other Klondikers who never hunted or fished. He provided salmon, pike, whitefish and trout for his own party and for other travelers. Often he gave surplus meat to Indians along the way.

Leaving Edmonton Wickwire’s party endured temperatures of forty below and sometimes worse. They fought their way through snow three feet deep, and were sometimes stopped by raging blizzards. Brush and timber had to be cleared – that promised road was nonexistent. Teams were doubled up in climbing steep grades after crossing rivers. Horses ran away; sleds upset, spilling their loads, and were often broken. The side of the trail was littered with ruined sleds, scattered belongings, and dead horses.

Some men, disheartened, dazed, perhaps half-crazed with fear, turned back toward Edmonton. Others packed what they could on their backs or on gaunt, weakened horses, and staggered on.

Many perished that year on the Edmonton Trail.

Wickwire and his partners found camping sites near feed for their herd, those Wyoming mustangs pawing deep in the snow to find grass. The barley was fed to the work teams and pack animals. Always, other parties camped nearby and there were many tales of troubles and disappointments.

They left the valley of the Saskatchewan, crossed the Pembina, the Paddle, and the Athabaska, followed the Swan River and Lesser Slave Lake, and reached Peace River. They traveled on the ice of the Peace River but, as the days warmed, that became hazardous with an overflow on the surface. Sleds were overturned, loads were spilled and soaked, hands and feet were constantly wet.

As spring came on they had pelting rain and sometimes high winds. And with the warm days came the flies and gnats, and mosquitoes in swarms so thick a man couldn’t breathe.

The Wyoming horse wranglers and other stampeders used the sleds on Peace River and for some miles up that stream.

THE PARTY DIVIDES

But on reaching Bear Creek, Wickwire and his partners faced reality. With no snow now and a break-up of the ice imminent, sledding was no longer feasible.

With 1,500 miles of the roughest terrain still ahead, getting to Dawson even by fall was now admitted an impossibility. A local trapper advised Wickwire and Lon to simply drop their horses. But Wickwire disliked leaving his horses to starve, and Weaver was adamant. He was continuing with his mules – if they died he would die with them.

Their trapper friend reminded them of another problem. Even should the horses get through, there would be no quick availability of pasture and feed for them at Dawson. It was decided to split the party, some heading for the Yukon by the quicker river route.

LIKE OTHER parties along the way they built a boat, having brought a whip-saw, hammer, nails, oakum and tar. Pitch they boiled from the sap of the pine trees. Their craft, which they dubbed the Wyoming, was smaller than most – just twenty feet by four feet – a choice which proved to be wise.

Charlie Olson left the group and joined another party and the Atkinsons returned to Edmonton.

On May 1 Weaver and Billy Hill, riding Roman Nose, headed into those massive mountains to the west, with the herd of mustangs and the six mules. They were horsemen, they declared, not boatmen.

So Wickwire and Lon were to go by boat and, reaching Dawson, would find feed for those horses when they arrived. In mid-May, after the break-up of the ice, they launched the Wyoming.

THE BOATMEN DEPART

Making good time downstream on the wide, swift Peace, they floated 500 miles and entered the Slave, a wild river with many rapids and falls. On the lesser rapids they chanced a run. Others required a portage of goods, with the boat let over with ropes. But the higher falls required a portage of both goods and boat. The portages were rough and exhausting. Usually several parties would work together.

At the more dangerous falls there were Indian guides for hire, but it was perilous work even for them. At a ten-foot fall just above Ft. Smith the Wyoming was grabbed by the current and Wickwire and Lon were catapulted through. They and the boat were miraculously unhurt. ”We were fools for luck” Wickwire said.

At Ft. Smith they teamed up with three Chicago men – Springer, Thomas and Fritz – who had a large 35-foot boat which they called the California. Towing the small Wyoming, they, crossed the Great Slave Lake which was very rough at times. They saw many other boats on the lake, filled with men hastening toward the goldfields, but many were lost in the bad storms.

On that long voyage they passed or stopped at numerous Hudson’s Bay posts: Dunvegan, Forts Vermilion, Smith, Resolution, Providence, Simpson, Wrigley. They found these posts in beautiful settings, with a store, a Catholic Mission, an English church, perhaps a school for Indians. They were interested in the different tribes who lived by hunting, fishing, and trapping, trading with the Hudson’s Bay Company. After reaching the Mackenzie River they saw a number of company steamers.

They entered the huge Mackenzie River on July 16.

At Ft. Good Hope they entered the Arctic Circle, and soon had that midnight sun. And they began seeing Eskimos. They followed the river 900 miles to its mouth at the Mackenzie Delta. There, at Ft. McPherson, they were joined by two Canadians, Cunningham and Tarleton, with their boat. They had met the two men in Edmonton.

Their route now led up the Rat River, a narrow rocky stream. They had to tow their boats with ropes, walking on the bank or, where the vegetation was too thick, take to the ice cold, swiftly flowing water and drag the boats. They were heading for that high point, MacDougall Pass.

Soon the big boats could continue no farther and Springer and Thomas, old and sick and scared, gave up. Fritz stayed behind with them. Hundreds of other travelers, hoping for survival now instead of gold, were forced to stop because of their over-sized boats- And born there on that wild mountainous creek was Destruction City.

Lon, Wickwire, Cunningham and Tarleton struggled on with the little Wyoming, finally making it through the narrow, rock-walled Rat River Gorge, the only party to succeed.

At last they were on the divide, and dragged the boat a mile and a half through brush and thick moss from the lake which headed the Rat to the lake which headed Bell Creek, flowing westward.

They rejoiced— this water would eventually reach the Yukon. From the mouth of the Rat to the divide they had covered but sixty miles and it had taken them twenty days.

Fighting down the narrow Bell Creek they entered the Bell River, then the big Porcupine.

After 250 miles they came to Ft. Yukon on August 27. Here, at last, was that river, the Yukon, which they had been aiming to reach for so many months. They felt lucky to be there, for winter wasn’t far away.

THEY SOLD their faithful boat for ten dollars and hired out as hands on the Oil City, a steamer loaded with kerosene and candles, bound up the river for Dawson. Wickwire and Lon now took time to wonder just where Weaver and Billy Hill were with the horses. Their own experiences helped them realize the problems those horse wranglers must be facing.

DAWSON CITY

They-reached Dawson on September 9, 275 miles out of Ft. Yukon. Wickwire and Lon had traveled 3,650 tough miles since leaving Wyoming almost a year before.

Hundreds died in that stampede to Dawson City. But Wickwire and Lon made it through, perhaps it wasn’t luck but a combination of good management, perseverance, and quite a dollop of daring. And being a pair of tough, seasoned Wyoming cowboys was a big asset.

After all they had endured, their arrival seemed like an anti-climax. And they weren’t surprised that they found no Wyoming mustangs there.

Dawson was a city of 40,000 people, all tents and cabins, with many saloons and dance halls. The Canadian Mounted Police kept very good order. Everything was very expensive but wages were good if a job could be found.

Wickwire and Lon stayed in Dawson, waiting to see if Weaver and Hill might possibly get through. Lon got a job with a mining company and Wickwire became a packer for Bartlett Brothers, freighters.

They soon found that hay, if it could be found, was $400 a ton, a pasture simply wasn’t available. They kept a close watch on the river, but by November they were certain there was no chance that the horse wranglers would arrive.

Wickwire and Lon worked on the Dominion Hill all winter and spring. In mid-June they came out with, although not a fortune, a good stake.

It was then that Wickwire, on the long street of Dawson, heard someone shout his name, and there was Fritz, their companion of the Rat River from nearly a year before. “I sure am glad to see you,” Fritz said. “You’ll never know how lucky you were to get out of there.” Wickwire heard his story of Destruction City.

Fritz said more men kept coming up the Rat River and were unable to go farther. With the onset of winter hundreds were there and they built cabins, and cut wood for fuel. There were enough provisions among them, but with no fresh vegetables or fruit, many got scurvy and died by the hundreds. Springer and Thomas died and Fritz buried them and marked their graves. He had found his way through to Dawson that spring with some Indians, but as far as he knew, no one else made it. Some went back down the Rat. But Destruction City was aptly named.

That summer of 1899 Wickwire again worked for Bartlett Brothers. As the days shortened that fall he and Lon gave up all hope of ever seeing Weaver and Hill – the horses had become secondary.

On September 25 the two men were watching the river boats and they sighted a raft coming down the stream. On it were two men, a horse and a mule. Something about that weary-looking group made them look again, and then they shouted. It was Roman Nose, the buckskin gelding, and one of Weaver’s mules. And with them were Weaver and Hill.

It was an exciting reunion. Wickwire and Lon’s relief was so great to see their partners safe that they didn’t give the loss of the horses a second thought. And they exchanged tales of their adventures.

Weaver and Hill, leaving St. John in early May of 1898, had first followed up the Peace River to Halfway River, then over the divide to Finlay River, and on to Dease River. Winter caught them, and they camped for the next few months in the Dease River country. The next spring they made it to Sylvester’s Lower Post, on to the Liard River, then to the Frances River. They pushed on to the big Pelly River and to Ft. Selkirk at the confluence of the Pelly and the Yukon.

They reached there with two head of stock – Roman Nose and the mule. For three days before reaching Ft. Selkirk they had lived on rose hips.

That terrible trek through the Rockies had been filled with hardship and peril. They crossed rivers with no fords, and broke trail through thick timber, deep canyons, and muskeg where the horses sank to their knees with every step. The men were often lost after leaving a river to cross a divide. They had rain and fog and mosquitoes and, when winter set in, biting cold and deep snow.

And, one by one or in groups, they lost horses. Some were killed in crossing dangerous rivers and deep chasms, in quicksand, in rafting down rapids, or hitting unexpected falls. Quite a number died that winter at Dease River. An Indian killed one for meat. Weaver killed the Indian and the Mounted Police fined him ten horses to be given to the tribe. Rafting down the Pelly with their ten remaining animals they hit a big cascade and lost all except Roman Nose and the mule. They also lost all their· supplies, beds, tents, and even their guns.

Weaver and Hill had traveled almost 1,700 rough miles since they left Wickwire and Lon at Bear Creek, and it had taken them over sixteen months. They didn’t believe any of the other parties they had seen on the Edmonton Trail even got through. And those Wyoming cayuses, tough and sure-footed though they were, had failed, too. Only Roman Nose had endured the 2,710 miles from Wyoming to Dawson.

Lon Taylor stayed in Dawson until sometime the next year. When he left, Weaver and Hill were still there and Lon told Wickwire later that Weaver was still telling his tall tales, and still laughing.

A few days after Weaver and Hill arrived, Wickwire headed for home, taking a steamer 1,800 miles down the Yukon to St. Michael at its mouth. Then, on a larger steamer, he traveled down the coast 2,700 miles to Seattle, and on to Wyoming.

HOME SWEET HOME

It was late fall before B.F. Wickwire reached Hyattville, and home.

The erstwhile Klondiker was welcomed but he found some changes. May, believing he had lost his life, had sold the ranch and moved to Basin. But Wickwire bought land on the outskirts of Hyattville and was soon back in the livestock business. In 1910 he laid out an addition to the town that is still known as the Wickwire Addition.

Leasing his ranch in 1906 he moved to Basin, the county seat, and went into the saddle and harness making business. Wickwire and May adopted a baby girl, Ruth, in 1907, the daughter of a minister whose wife had died.

B.F., as he became called, was appointed sheriff of Big Horn County in 1911 and, consistently reelected, served the county until 1923. It was a period of great growth in that area, and also the time of prohibition which multiplied the problems of law enforcement officers. B.F. handled those situations with the same good sense and efficiency he had shown on that long-ago trek to the Yukon.

Wickwire returned for a time to his ranch at Hyattville but in the thirties he leased it. He and May moved to Thermopolis, that Wyoming town of medicinal hot springs.

He sold his ranch in 1940, and the many years when the Wickwire name was on Paintrock-Medicine Lodge ranch land ended.

Wickwire’s daughter Ruth and her husband, Wallace Chesbro, were living in Casper and in that city B.F. Wickwire spent his last years, enjoying his daughter and two grandchildren, Wallace Jr., and Joann. He died in Casper on March 25, 1943 at age 79. May outlived him by a number of years.

B.F. Wickwire lived at a time filled with possibilities for high adventure, and he wasn’t one to stand on the sidelines. His was a life of action and purpose, accomplished, like that trek to the Klondike, not so much because of the good luck he was so prone to crediting, but because of common sense, good humor, and plain hard work— With a good dash of daring.

THE END